Mindfulness Meditation

What is Mindfulness Meditation?

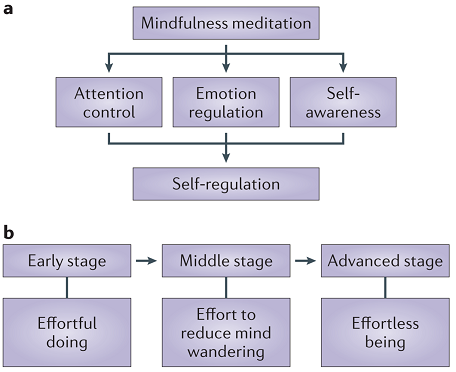

Meditation is a form of mental training that aims to improve an individual’s core psychological capacities such as attentional and emotional self-regulation. Meditation includes a variety of activities including mindfulness meditation, mantra meditation, yoga, tai chi and qi gong. Mindfulness meditation is described as non-judgemental attention to present-moment experiences and is the technique most intensively scientifically researched to date (Tang et al 2015). Mindfulness Meditation can begin as a guided session with an instructor in an individual or group setting, evolving to a personal practice of silent open-eyed seated meditation paying attention to present moment sensations and returning to concentrating on the inhale and exhale sensations of the breath through the nose whenever the mind wanders.

Image courtesy of Tang et al 2015

Although it has been used in ancient Eastern practices for aeons, it has gained popularity in the past two decades within the Western world and scientists are now researching its beneficial effects as well as its physical impact on the brain (Tang et al 2015) and on biomarkers (Sanada et al 2017). It is increasingly being implemented as part of holistic health care programs for disease prevention and chronic disease management as well as being recommended in clinical practice guidelines (Greenlee et al 2015) and reducing age-associated brain changes (Chételat et al 2017).

Among the documented benefits include improved quality of life and improvements in mood, anxiety and depression scores. In cancer, it has been investigated for the management of cancer-related pain (Ngamkham et al 2019) as well as anxiety and depression related to diagnosis and treatment (Bower et al 2015 and Zhang et al 2015 and Boxeleitner et al 2017) and the impact on overall quality of life and well-being (Chang et al 2018).

What are the Changes Seen in the Brain?

Using functional MRI (imaging the brain to see changes in blood flow which indicates the amount of activity in that part of the brain) to assess brain activity during meditation, there appears to be three areas with clusters of activity (Sperduti et al 2012):

Caudate: attentional disengagement

Parahippocampus: controls mental stream of thoughts

Medial prefrontal cortex: supports enhanced self-awareness

Mindfulness is therefore thought to act on three areas; attention, emotion regulation and self-awareness.

Mindfulness and Attention

Early phases of mindfulness meditation are thought to improve conflict monitoring and orientation which means that the brain is learning how to decipher between the conflicting demands on attention and steer its focus by choice rather than by default. Once that is mastered, later phases of mindfulness meditation are thought to be associated with improved alerting which means attention and distraction is no longer an issue and awareness or alertness is enhanced (Chiesa et al 2011).

Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation refers to strategies that can influence which emotions arise and when, how long they occur and how they’re experienced and expressed. The positive effects of mindfulness meditation on emotional processing includes reduced emotional interference by unpleasant stimuli, reduced physiological reactivity, facilitated return to baseline after stress, reduced self-reported difficulties in emotion regulation, lowered intensity and frequency of negative effect and improved positive mood states (Tang et al 2015).

The other interesting aspect to note is that novice meditators have different areas of brain activity than expert meditators. For example, novice meditators have reduced activity in the amygdala (emotional arousal), enhanced prefrontal activation (emotional control) and activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula (nociceptive processing and reframing evaluation of stimuli). This indicates that novice meditators become proficient in emotional regulation or control (top-down) but expert meditators become proficient in emotion acceptance (bottom-up).

Mindfulness and Self-Awareness

Identification with a static concept of Self often is a cause of psychological distress. Disidentification from a static concept of Self results in the freedom to experience a more genuine way of being. Mindfulness training is associated with a more positive self-representation, higher self-esteem, higher acceptance of oneself and styles of self-concept that are typically associated with a reduced severity of pathological symptoms and less attachment.

Another interesting area for research is the Default Mode Network. This is thought to consist of the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the anterior precuneus and inferior parietal lobe. It has high activity at rest and is the default mode of thinking so to speak. It is responsible for the mind wandering and for stimulus-independent thought. Functional MRI studies demonstrate diminished activity in the DMN in those who meditate compared with those who do not meditate. This translates to reduced self-referential processing (self-centredness, identification with Self) due to improved cognitive control over the DMN.

What are the Clinical Benefits?

The clinical benefits of Mindfulness Meditation on cancer-related outcomes are both direct and indirect. Directly, there are improvements in anxiety, depression and distress caused by the diagnosis and treatment. When anxiety is effectively managed, there is improved quality of life, better psychological adjustment, understanding of the disease and decision-making as well as adherence to treatment. It has also been proven effective against pain and other symptoms of the disease and treatment.

The other important function to note is that improved anxiety and distress leads to improved immune system function and better immune surveillance and fight against cancer cells and recurrence as well as enhancing the speed and quality of healing and repair of the body as it shifts from a state of fight or flight (sympathetic) to rest and repair (parasympathetic).

What is the Evidence?

Anxiety and Depression

Greenlee et al (2018) published clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and following breast cancer treatment. They analysed 5 RCTs published between 2009 and 2013 that compared meditation with usual care for breast cancer survivors and found meditation to improve anxiety levels. They’re clinical practice guidelines support the use of a meditation program for anxiety and depression in cancer.

Bower et al (2015) conducted an RCT investigating the use of a 6 week mindfulness intervention against a usual care control in women younger than age 50 who had completed treatment for early breast cancer. The investigative arm had reduced levels of perceived stress and even more interestingly, reduced levels of pro-inflammatory gene expression (p=0.009) and inflammatory signalling (P=0.001) than the control group as well as reduced fatigue, sleep disturbance, vasomotor symptoms and increased peace, meaning and positive affect. The other interesting aspect to note is that these changes were seen for the pre and post-intervention questionnaires but not sustained at the 3 month follow-up questionnaire which suggests that these changes persist only as long as the person’s individual practice continues.

A Meta-Analysis by Zhang et al (2015) found similar results for anxiety and depression. It included 7 studies and pooled results of 469 participants and found that mindfulness-based interventions improved anxiety and depression scores compared with the control group but this did not persist at 12 weeks when the intervention was no longer being implemented.

Cancer Pain

A systematic review by Ngamkham et al published in 2018 reviewed mindfulness intervention for cancer-related pain. It found 6 studies published between 2015 and 2017 varying in study population between 38 and 322. The participants were affected by breast or colon cancer and located in the US or Denmark. Mindfulness-based interventions were thought to reduce pain severity, anxiety, depression and improve quality of life.

Immune Function

A systematic review conducted by Sanada et al and published in 2017 analysed the effect of mindfulness-based interventions on biomarkers in both healthy individuals and those affected by cancer. Reviewing 6 publications that included 360 participants, mindfulness-based interventions were found to alter cytokine production into a more favourable profile for immune function against cancer.

Recommendations

Mindfulness Meditation is recommended to be implemented for two sessions per day at 30 minute intervals. This is ideally done sitting in silence with alertness and attending to present moment sensations returning to the inhale and exhale sensation of the breath when the mind wanders. It is suitable to use a guided session with an instructor in an individual or group setting to become well trained for personal sessions. As always, consultation with a qualified meditation teacher or instructor or an integrative consultant is beneficial as are referrals to group services and programs.

It is further important to note that the classical appearance of meditation can be intimidating at first and this will improve with continued practice. Mindfulness Meditation can also be incorporated and practiced throughout the day by bringing attention to the present moment experience of whatever it is being done eg washing dishes, walking from one place to another, playing a sport. It can take many different appearances and one should not be discouraged if the classical format feels unsuitable. Seek guidance for alternative practices that can achieve similar results from being mindful exactly how and where you are.

References

Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(4):213-225. doi:10.1038/nrn3916

Sanada K, Alda Díez M, Salas Valero M, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on biomarkers in healthy and cancer populations: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):125. Published 2017 Feb 23. doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1638-y

Chételat G, Mézenge F, Tomadesso C, et al. Reduced age-associated brain changes in expert meditators: a multimodal neuroimaging pilot study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10160. Published 2017 Aug 31. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07764-x

Greenlee H, Balneaves LG, Carlson LE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast cancer [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2015 May;2015(51):98]. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014(50):346-358. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu041

Ngamkham S, Holden JE, Smith EL. A Systematic Review: Mindfulness Intervention for Cancer-Related Pain. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(2):161-169. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_67_18

Bower JE, Crosswell AD, Stanton AL, et al. Mindfulness meditation for younger breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in Cancer. 2015 Jun 1;121(11):1910]. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1231-1240. doi:10.1002/cncr.29194

Zhang MF, Wen YS, Liu WY, Peng LF, Wu XD, Liu QW. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Therapy for Reducing Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(45):e0897. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000897

Boxleitner G, Jolie S, Shaffer D, Pasacreta N, Bai M, McCorkle R. Comparison of Two Types of Meditation on Patients' Psychosocial Responses During Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;23(5):355-361. doi:10.1089/acm.2016.0214

Chang YY, Wang LY, Liu CY, Chien TJ, Chen IJ, Hsu CH. The Effects of a Mindfulness Meditation Program on Quality of Life in Cancer Outpatients: An Exploratory Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):363-370. doi:10.1177/1534735417693359

Sperduti, M., Martinelli, P. & Piolino, P. A neurocognitive model of meditation based on activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Conscious. Cogn. 21, 269–276 (2012)

Chiesa, A., Calati, R. & Serretti, A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 449–464 (2011)